Scientists collaborating on antifreeze protein experiments at UNH to explore ice-binding properties for medical and agricultural applications.

Research Goals

Found widely in nature, including in fish, plants, fungi and insects, antifreeze proteins (AFPs) inhibit the growth of ice crystals by binding to ice surfaces. By studying the mechanisms that enable AFPs to bind ice and affect its properties, University of New Hampshire researchers are examining how these proteins could improve modern cryopreservation methods for preserving cells.

In the depths of winter and in some of the coldest places on Earth, certain life forms—like fish swimming in icy waters or plants rooted in frost-covered soil—remain unscathed by freezing temperatures that would otherwise rupture cells and end life. Many of these organisms owe their survival to antifreeze proteins (AFPs), natural compounds that inhibit large ice crystals from forming in their tissues. Found across a range of organisms—from bacteria and fungi to insects, plants and fish—AFPs allow these life forms to survive freezing environments or freeze-thaw cycles by lowering the freezing point of water and preventing ice crystals from growing. Now, with the rapid advancements in regenerative medicine and biotechnology, researchers at the University of New Hampshire (UNH) are exploring how these ice-defying proteins might unlock safer, more effective methods to preserve biological materials in medicine and biotechnology.

Krisztina Varga, an associate professor in the department of molecular, cellular, and biomedical sciences at UNH’s College of Life Sciences and Agriculture (COLSA), is leading research to adapt AFPs for use in freeze-sensitive applications. Her work could provide a breakthrough alternative to traditional cryopreservation agents like dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), which can cause adverse reactions in patients. By exploring AFPs' potential in preserving cells and tissues for transplants, as well as in extending the shelf life of frozen foods, Varga’s research aims to bring these natural adaptations into practical, transformative use.

“I’m interested in understanding how organisms can survive extreme environments—like extreme cold, extreme dehydration, or extreme heat,” Varga said. “The antifreeze proteins are part of how nature solves this problem, helping these organisms live in conditions that would otherwise be deadly.”

She added, “By studying how these proteins’ function under natural conditions, we’re uncovering new applications in medicine and food technology that could ultimately benefit regional industries right here in New England.”

Central to Varga’s research is understanding how AFPs selectively bind to ice crystals, inhibiting further crystal growth and reducing potential cell damage. This function is critical for regional species like snow flees (Hypogastrura nivicola) and winter flounder (Pseudopleuronectes americanus), which use AFPs to prevent large ice crystals forming in their blood and tissues, thus enabling survival in sub-zero environments. Similar adaptations are also seen in plants like winter rye (Secale cereale), which withstand frost damage to survive and grow during cold seasons.

Aiding Varga in this research is a team of postdoctoral scientists and undergraduate and graduate students — among them doctoral student Jack Sylvester, whose passion for winter sports complements his scientific curiosity about how organisms endure the extreme cold.

“I remember skiing in Vermont’s Green Mountains on an especially cold day,” Sylvester recalled. “It was a challenge just to stay outside for more than an hour. That experience, and my fascination with how life persists in freezing environments, has really inspired my research into antifreeze proteins.”

Since 2024, Sylvester has focused on studying the cryoprotective properties of antifreeze proteins found in plants.

“We’ve been exploring how these proteins might be used to cryopreserve mammalian cells,” he explained. “This research could one day pave the way for long-term organ preservation, revolutionizing how we store and transport vital biological materials.”

Advancing Cryopreservation and Beyond

Understanding the unique ice-binding properties of AFPs could lead to safer, more effective freezing methods for cells, tissues and organs. Currently, organ cryopreservation isn’t feasible due to ice damage, and cell preservation relies on the chemical DMSO, which is toxic to cells at high concentrations and may cause certain stem cells to unintentionally transform into other cell types. AFPs offer a potential alternative to DMSO, promising safer, more effective cryopreservation. AFPs are already used in the food industry to prevent large ice crystals from forming in foods like ice cream, helping to maintain the texture of the food and extend its shelf life.

In the lab, Varga and her team replicate AFPs and study their structure in detail. Using tools like Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, they investigate the molecular structures responsible for AFPs’ unique ice-binding capabilities to better understand how these proteins recognize and interact with ice. They also study their functional characteristics, such as ice-recrystallization inhibition, which prevents ice crystals from growing larger, and thermal hysteresis, which controls the temperature at which ice crystals grow.

“By understanding the structure of these proteins, we’re uncovering the precise mechanisms that make AFPs so effective at controlling ice,” explained Varga. “This insight allows us to see how AFPs bind to ice, which is essential for advancing our work in cryopreservation.”

Interdisciplinary Collaborations

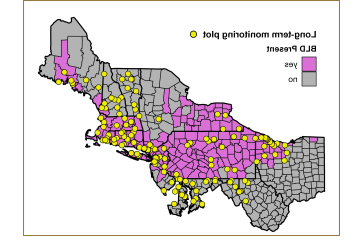

Varga works with several UNH scientists and centers to expand the impact of her research on antifreeze proteins. Jessica Ernakovich, from the department of natural resources and the environment at COLSA, collects ice, snow and soil samples from the Arctic region. Back at UNH, these samples are processed in collaboration with the Hubbard Center for Genome Studies (HCGS), where Varga and Ernakovich use genomic sequencing to identify potential antifreeze proteins in them.

“My research focuses on the microorganisms that live in perennially frozen Arctic soils—called permafrost soils—and how they change as permafrost thaws due to climate warming,” explained Ernakovich. “However, exploring how antifreeze proteins contribute to the survival of these microorganisms is a fascinating extension of this work, and collaborating with Dr. Varga on this research offers an exciting opportunity to uncover the mechanisms that these organisms use to endure extreme Arctic conditions.”

Another collaborating UNH scientist is John Tsavalas, an associate professor in UNH’s chemistry department. Tsavalas has developed polymers – molecules made up of smaller repeated and chemically bonded units – with properties that mimic the properties found in AFPs.

“Nature sets the gold standard, and the structural elements Krisztina identified in the antifreeze protein were essential to our design of a simplified, synthetic analog inspired by these natural mechanisms,” said Tsavalas

In the future, Varga plans to work with members of COLSA and UNH Extension to explore whether insects found in local forests might produce AFPs. Many of these insects are also agricultural pests, so identifying AFPs in these species could provide new insights into managing their impact on plants. Collaborators on this project will include Jeff Garnas, an associate professor of forest ecosystem health at COLSA; István Mikó, director of UNH’s Collection of Insects and Other Arthropods; and Amber Vinchesi-Vahl, a UNH Extension specialist in entomology and integrated pest management.

Through these collaborations, Varga is paving the way for antifreeze proteins to have transformative impacts across fields ranging from agriculture to biotechnology.

“Antifreeze proteins could one day offer applications beyond preservation—from keeping organs viable for transplant to developing frost-resistant crops that better survive changing climates,” she said. “They might even aid in long-duration space travel, where cryopreservation would be crucial. We’re just beginning to unlock what these proteins might make possible in medicine, agriculture and beyond.”

Varga’s work has been supported by funding from the National Science Foundation (NSF), National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), and the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Learn more about the research taking place across UNH's College of Life Sciences & Agriculture on UNH Today.

-

Written By:

Nicholas Gosling '06 | COLSA/NH Agricultural Experiment Station | nicholas.gosling@391774.com